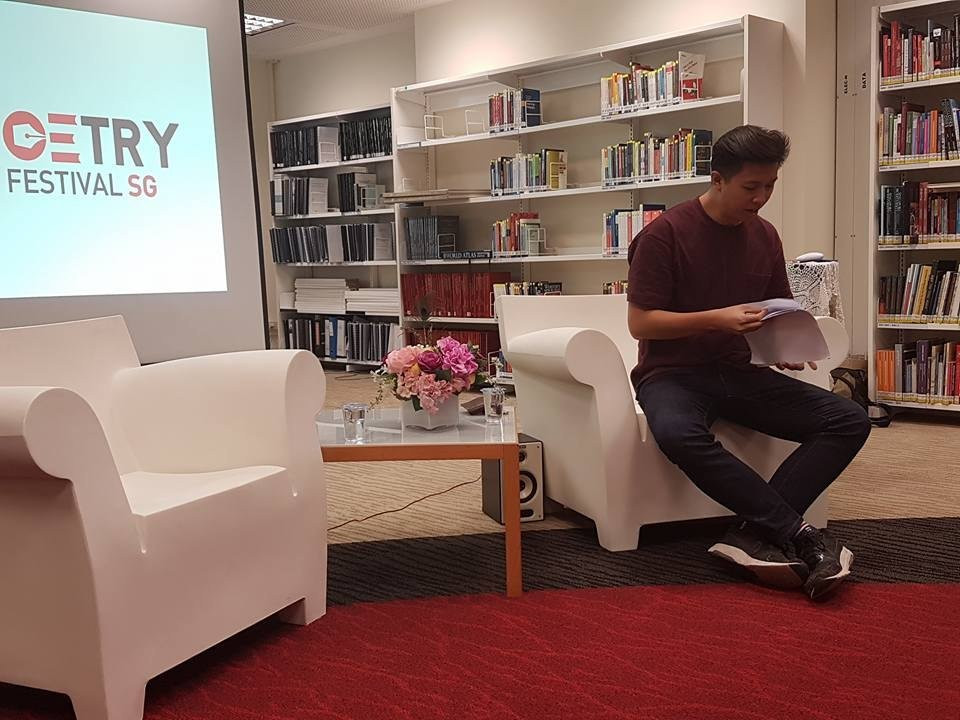

The first time I saw Samuel Caleb Wee was when I was tip-toeing my way through a glass door because I was late for the ‘Youth Is Wasted On The Young’ poetry reading at the Woodlands Library.

It took me a minute to shuffle into the back row, and for my mind to gather the sounds my ears were picking up on: wait, is he singing?

Samuel Caleb Wee has edited an anthology of experimental fiction ‘this is how you walk on the moon’ (2016) , recently completed his master’s degree degree in English Literature at NTU, and is now working through his debut poetry manuscript. Last year, he worked with a local musician, Zhongren Koh, from the band ‘Plate’ for a tête-à-tête between poets and musicians: Note For Note. “Collaborating with musicians who are close to the membrane between art forms is a sort of cross pollination”, he says, “of verse and rhythm.”

There was a certain rhythm to our conversation too. It took place before he left for Vancouver for his PhD, at the coffee shop in the Jurong library. He insisted we order something. So, a basket of french fries sat between us. Samuel would make cutting rejoinders, fall silent to listen to himself, then sit up straight again, piquing my questions into organic conversations which surfaced more of his rich voice.

He started writing poetry during his creative writing classes at Nanyang Technological University (NTU): “There used to be this journal called ‘Ceriph’, run by Amanda Lee Koe. It was my first initiation into the literary scene. I participated in their arts project called 10 By 10. It was quite enjoyable.”

10 By 10 was a community arts project which paired young writers with senior citizens to collaborate creatively over six weeks. Some participants like Daryl Yam and Min Lim are still writing.

“I mean I was always writing in some capacity or the other - not very well back then; maybe not very well now. But the instinct to write has always been companion to the instinct to read. I have this kind of arrogance where if I see something, I think, oh I could do that, or I want to figure it out by trying to unpack it somehow.”

He adds that journalism has always been on the side-lines. “It pays the bills.”

Samuel also caught the travel bug during his undergraduate degree. “I like to travel because it's a reminder that the realities you take for granted are not set in stone. Something could be completely inverted elsewhere and your normal is not someone else's normal. I'm not a travel writer like Boey Kim Cheng is, but I do take a lot of inspiration from the people I meet. When you travel, you're always meeting people who are in between worlds, people who have fallen out of their lives in some interesting ways and sometimes you fall out of your world in interesting ways.” Pause. “I like that. I like being out of context.”

Image credit: Jay Jay Lin - At the book launch of this is how you walk on the moon: an anthology of anti-realist fiction

When asked to describe his own work, Samuel positioned himself between introspective and outward looking. It isn’t confessional in the way Christine Chia’s or Cyril Wong’s is, but an element of what happens to him or inside of him, goes into it: “An intersection of my interior world, an external world, and some other kind of ethereal artistic world that all come together.”

Samuel used to be religious when younger, and then fell out of it. It influences the way he thinks and writes – a circling around the loss of a God in some sense. With his beliefs on religion altered, a definite morality is something he thinks about a lot.

“I don't mean we shouldn’t make ethical choices as human beings. People want to hold onto the idea that they are good people and that's the biggest lie you can tell yourself. The self is such a huge fiction, such a complex combination of different things that at no single point can you claim to know yourself - so the desire to think of yourself as a good person is really just a desire to reduce your story to one single narrative that you approve of, which means that you're making yourself lying to a lot of other things about you.”

Pause.

“I’m quite neurotic. So I want to be self-aware. Clearly, I'm very neurotic [his face scrunches as he stares down at the fry he’s been munching on] What’sInTheseFriesAmIHigh?”

“Nowadays I don’t feel like I need to propagate some kind of moral lesson in my writing anymore.” He continues, “I’m just really interested in making things.”

“Is morality a pre-requisite for art.” I comment.

“Ah you got that from my poem,” he laughs.

I remember Finals - a conscious and clever poem - and ask him if he is naturally inclined towards experimenting with form while writing.

He smiles. “I do like to mess around. I do like a bit of slippage, a bit of chaos, but I don't consider myself as being very experimental. My poems take whatever form they need to take, and other people look at it and think it's very whacky or far out, but I don't necessarily put it that way. I don't contextualise my work, but other people do.”

Samuel is now working on a new manuscript. “The old manuscript was dialectical text where I was struggling and working through a lot of opposites. There are points in the text where you get whiplash in going from one extreme to the other and I was intentionally trying to play with that effect in the hope that at the end of it you find, if not resolution, at least some kind of synthesis to leave off on. So, parts of the text are weird, but parts are very traditional as well.”

When asked what kind of poetry he likes to read, he says: “It's not so much about the classification of the poem. It can be funny, terrifying, heartbreaking – often all at the same time. Anything, as long as it gets me to respond on a visceral level. There’s a poem I love by Maggie Smith called Good Bones. It’s very emotional and moving - across a wide array of emotions.”

Samuel also performs spoken word poetry. Page poetry allows an intimate space to enter the text and co-create it. Spoken word, too, is organised around deliberate pauses of silence. I ask him what he thinks of the two forms.

Image credit: Jared Ho

“I like hanging out at the Beast. There's this weekly open mic on Thursdays so I step by and play music. People are often comparing page poetry and performance poetry but they’re two completely different stylistics- there are elements that go into a performance that you necessarily can't get on the page. ”

He gushes about a performance at Destination Ink, by Bill Moran from Texas, that completely blew his mind: “It consisted of Bill trying to introduce himself, but the performance was that he couldn’t complete his sentences. So you didn't know what the hell was happening for the first five minutes! The presence of a body is very important for spoken word. It was all very masterfully done.”

Samuel also started to meet like-minded people by going for open mics at Destination Ink: “I’ve made so many friends just showing up and talking to people and getting blindingly drunk. I don't think anything will ever replace going to a physical space, shaking someone's hand and buying them a drink.”

“There’s lots of opportunities to meet like-minded people now. The SingPoWriMo kids [from the Singapore Poetry Writing Month facebook group] are very inclusive to new folks coming to the discussion. It’s grown a lot from back in my time. God I keep sounding like I'm really old.” He laughs and shakes his head in mock misery.

The Singaporean literature scene is exploding. But he does wonder if there’s “enough blood and bone and viscera in it, if it's messy enough.”

“I think people have a fear of being hidden or obscured. People want to be visible and get out there. Someone who represents a minority might want to be visible because they want to bring representation to the table. And that's important. I empathise with that. Sometimes, I do wonder if that concern for visibility holds people back from making other artistic choices that they would otherwise make. Regardless of how cerebral you make your poetry, people are going to read it biographically sometimes, and that's why they hold back on certain kinds of poems - because they don't want to be put in that light: that they are thinking of these questions which might not the right things to think or the right questions to ask. So what I'd hope for is a sort of community in which people don't mind asking dangerous questions and don't mind saying dangerous things. Ask questions that matter, and those that do not.”

“I think you also need to have freedom to ask questions that don't matter immediately in the conversation, questions that people might think are useless or frivolous. It is counterproductive to say that we should only talk about specific things, because poetry is not about the immediate, poetry is not about the news headline.”

Eventually, it’s time to leave. I ask him if there’s anything he struggles with in his creative life and how he deals with it.

Samuel draws a deep breath and laughs.

“I guess my challenge is not to be shit lah.”

He shifts in his chair. “The challenge,” he continues thoughtfully, “is to find voices that you trust, voices that you respect, to give you feedback. Sometimes you write something, and people find it shit. Your challenge is deciding whether you want to stick to your ego or take someone's feedback and mutate. I think, ideally, you would always be changing in ways you don't expect. Simultaneously, as you grow in your pursuit of your craft, your friends might be changing as well. Sometimes, you might come to a point where you think “wow their journey is not my journey”, and then the trick is learning to disengage gracefully, without making much of a mess."