"Go on. I dare you. Pull the trigger."

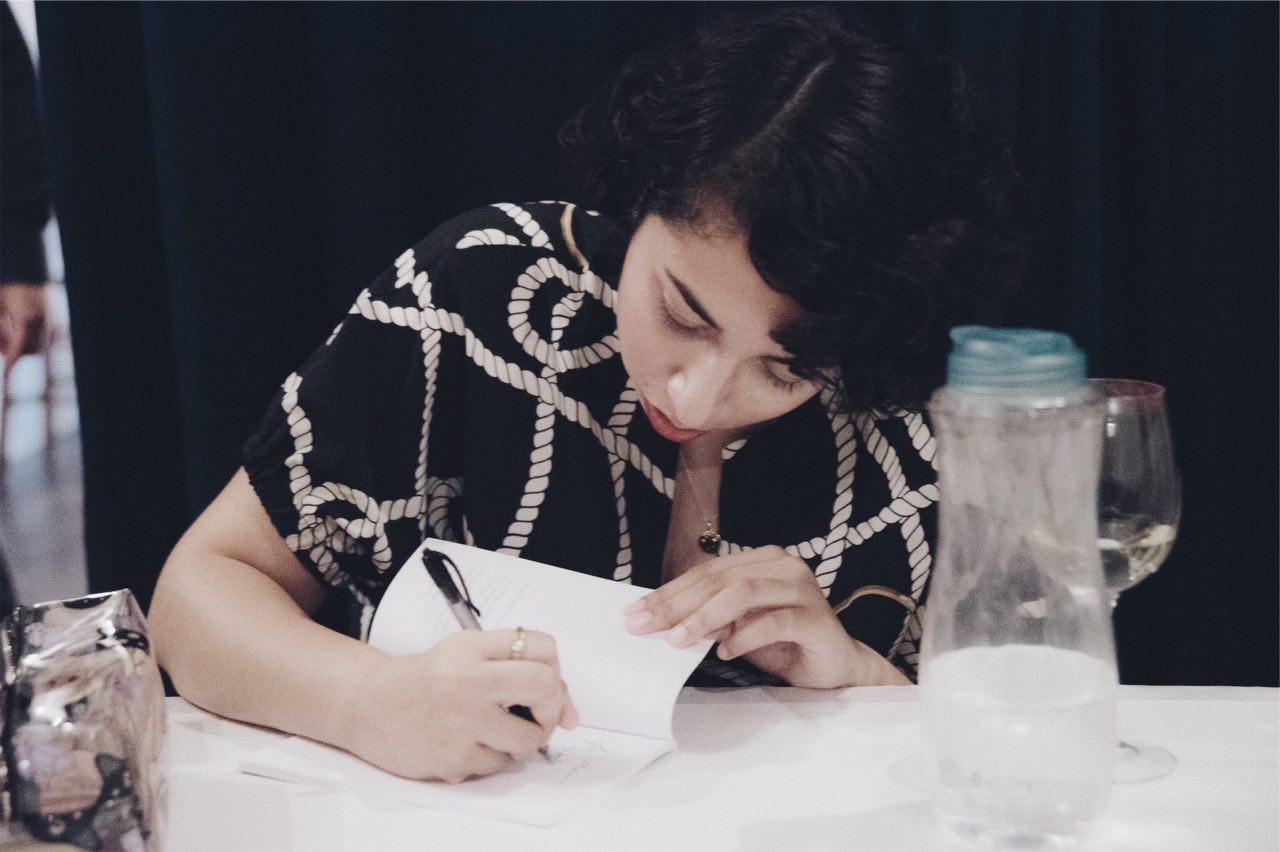

Meet Topaz Winters: poet, essayist, editor, creative director, speaker, scholar, actress, artist, and Princeton University undergraduate studying Literature and Film.

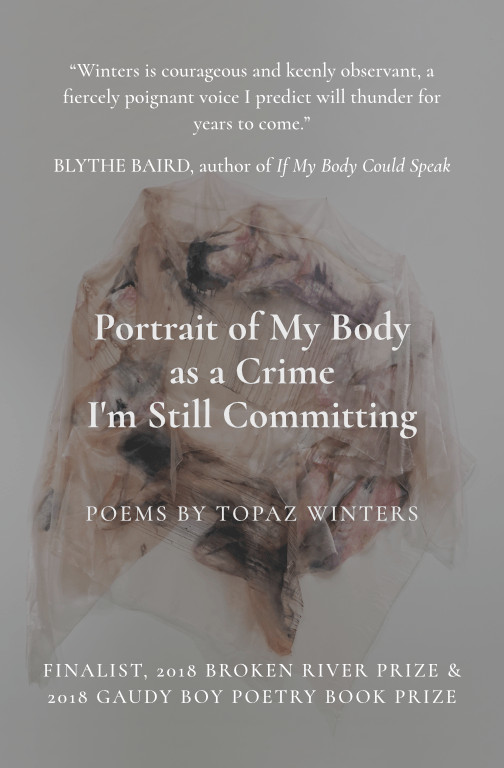

Topaz’s latest collection of poetry, titled Portrait of My Body as a Crime I’m Still Committing, revolves around the immediacy of language, girlhood as wolfhood, the cartography of illness, fractures through the dark, and bodies, both human and water.

STYLEGUIDE talks to Topaz Winters as she shares on her poetry, experiences, and journey of creation.

How did the name “Topaz Winters” come about?

It’s a variation on two nicknames given to me separately by two people I loved very much. I adore having a pen name; it separates my artistic work from the rest of my life, particularly since a great deal of my poetry is profoundly, uncomfortably personal. It helps me maintain strong boundaries when in every other sense that can be incredibly difficult.

Whenever I sit down to create I think of the two people who, in their own ways, indirectly named me, and I’ve come to believe this is how sunrise lives in the body, or how softness does, or hope.

"I’m waiting for you in the future tense,

with the words in my hands & strung

around my neck. Would you believe me

if I told you it wasn’t supposed to end like

this?"

The imagery you conjure in this collection is very material, very human, and very physical. What is the inspiration behind this focus?

The journey to this manuscript centred in many ways around allowing myself to viscerally sit with my emotions without rationalising them or insisting to myself that they had to make sense. I’m not sure whether it’s a tendency shared by mentally ill people in general or specific to me, but I’ve found that when my emotions overwhelm me, I cope by reminding myself why they’re unnecessary or invalid—a strategy that might work in the moment but so quickly becomes destructive and silencing in itself, just another method to reach across non-existent distance.

In this book, I tried to open myself to the physicality of my hurting, my panicking, my running, and my loving. There’s a desperate humanity nestled in that act that previously I shied away from—but these days I am tired of putting reason to my need.

Sometimes I just need. Sometimes that’s enough.

In the epigraph, you mentioned that Portrait is dedicated to ‘the girl you were before.’ Why was it so essential for you to address that part of your past, and what lessons has that journey brought you?

I’ve spent considerable time in my life doing all manner of wild and senseless things in a search for healing. The girl I was before all this hurt descended—before I had anything to heal from—might look at these poems and feel embarrassed, want to curl into herself.

The book is dedicated to her because I think in some sense I do miss the days when I did not lay down on my illness like knives in the ground, when that elusive “before” was in present tense and I barely knew the meaning of night—but it’s also dedicated to her because, stunningly and shockingly, whether she’d want to acknowledge it or not, she brought me to the formidable now.

Portrait is dedicated in equal measure to that girl and the ‘before’ she inhabited.

I’m grateful for all the mistakes she’s made. I’m grateful she chose to stay.

How do you think your experience in dealing with mental illness has influenced your writing?

Mental illness is so hard on its own, but it’s even harder when put in context with the complex ideas, reactions , and opinions of neurotypical people. Goodness knows the ones I love have hurt me with their words about my illnesses, but also, I have hurt them back.

I can’t assign a villain in this story, though in the moment of [the poem ‘When My First Boyfriend’] the villain might be clear-cut.

In the end, we choose the way we love, andI’m trying to choose a love that’s forgiving, that holds me and the people in my life accountable while simultaneously allowing us all room to grow. It’s a tough balance—of course, we shouldn’t keep people around who consistently trivialise our illnesses and make us feel devalued—but the people I choose over and above all their mistakes, and vice versa, are there for a reason. And I believe those reasons are worth fighting for.

"Sick or sane, the forest is beginning

to listen in on our shatterings."

What made you first decide to write in the confessional style, and why did you also decide to include elements of manifesto in your work?

There was never really a moment wherein I made the conscious choice to write in a confessional style—I think I just tend to naturally gravitate to that style of poetry (perhaps because even before I started doing this professionally, writing was always the way I processed my experiences and feelings!).

The manifesto-like element of Portrait is definitely far more deliberate, though. So many of the emotions in these poems arose out of running away from loudness because it was scary and bright, unfamiliar and uncomfortable.

I wanted the words I wrote afterwards, the ones that memorialised the encounters where more often than not I shied away from speaking my truth, to have an opinion, a sound, no matter how deeply it scared me. If the root of this book is silence, I hope the form is voice.

Girlhood and gender are very central themes in your work, both present and past. As someone with a wide readership, do you think it is vital to portray femininity and the female identity as truthfully as you can?

I wouldn’t claim that portraying the female identity as a singular truthful construct is particularly vital to me, simply because I don’t know most of the female identity! I’m only one woman, and I can’t place on myself the enormous burden of representing an entire gender’s spectrum of experience in my poetry.

With that said, I certainly try to portray my own femininity as truthfully as I can, the same way I try to portray my own yearning truthfully, my own forests and gardens, my own darkest fears and first loves. I try to share my tiny, unique experience of femininity rather than worrying about portraying the enormous, glorious, terrifying, multifaceted wonder that is the entirety of the female identity.

I think in my work, what I’m trying to say is: listen. This is how it feels to me. Can you hear me? Does it feel the same way to you?

"I know this moment soft,

like a wolf knows the taste

of its own hunger in the dark."

How do you navigate and assert your identity as a queer woman in your work, especially in relation to certain cultural and social standards prevalent in Singapore?

I believe at the core, my queerness and womanhood are inextricably linked, but I’m also learning to forgive myself when the link itself shifts in its definition, its reaching out, its becoming. There are times when the dynamic between these two aspects of my identity feels like a terrible heat, and there are times it feels soft as rain on windows, and I must always remind myself that neither is wrong.

I don’t necessarily see my work as an assertion of queerness or of womanhood so much as I see it as an exploration of both together. Of course, there are opinions all around about what that link should be or do or look like, but I try not to listen too closely, or let the noise affect the organic evolution of my identities and the way I express them.

I’ve found I bloom best when not under constant scrutiny.

What do you hope people understand or take away from Portrait?

Fists and their consequences. A hunger that can’t be satiated with food. The innumerable names for tenderness. A danger unspooled through the teeth, grounded in helpless love for something that might never have existed. A talisman. Hope, and every way it surfaces on the bloodied horizon. A song that never finishes, or barring that, one that replays again and again. Girlhood as wolfhood. The incredible blessing of want. A country made entirely of sunlight. Teeth, and memory, and longing. Always a flame but rarely the colour you’d imagined it. The sweet and tenuous music of not being alone anymore. Permission to breathe. Forgiveness for the things undefined, unnameable. Anything but silence.

"Did I say mourning?

No. This is a story

about survival.

How brilliantly oversalted,

this land with no remedies,

no faiths or monsters.

All I know is having a body

can only be an act of hospitality."

Buy Portrait of My Body as a Crime I’m Still Committing, and follow Topaz on her website, Twitter, and Instagram.

Photos and poetry excerpts courtesy of Topaz Winters.